The History of the Ned Kelly Gang

Written by Ronald Land

Once we know the stories of our ancestry, they emerge in the most interesting places. It happened to me when I heard about the Australian Seminar evening at Trinity College in Dublin. That’s because I’m the great-grandnephew of the police officer in command during the capture of Australian outlaw Ned Kelly.

Ned Kelly was undoubtedly the most well-known wholesale horse thief, bank robber, police murderer, and all-around folk hero in Australian history. Read on to learn more about him and the Kelly Gang and how their story became entwined with my family’s history.

Who Was Ned Kelly?

The Ned Kelly Gang were bushrangers who terrorised the population of the northeastern district of Victoria, Australia, from 1878 to 1880. The gang’s leader, Edward ‘Ned’ Kelly, was eventually captured by police under the command of my great-granduncle, Superintendent John Sadleir.

John Sadleir wrote about the gang many years later in his book, Recollections of a Victorian Police Officer:

“The true picture of the bushranger shows him to be a very poor and sordid thing indeed. The Kellys, in spite of a few successful enterprises, were as poor and unheroic as any of their kind. The more one reflects on the circumstances of these enterprises, the more one wonders on the timidity and faint-heartedness of the people they had to do with, and that made these successes possible.”

Yes, Ned Kelly was a real person, and his story is true. Below, I’ll share more about the true history of the Kelly Gang and events that occurred from my ancestor’s perspective.

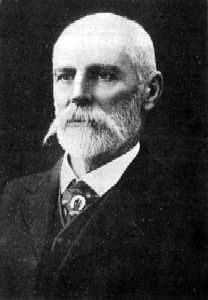

Who Was John Sadleir?

John Sadleir was born in 1833 in Brookville House, a mile south of Tipperary Town in Ireland. His father was a tenant farmer, his uncle Nicholas was a solicitor in Tipperary and Dublin, and he was the maternal grandfather of Admiral of the Fleet David Beatty.

In 1852 at age 19, John decided to emigrate to Australia. My great-grandfather, 17 years old at the time, made the journey too. My great-grandfather tried digging for gold before going into farming. John went straight into the Victoria police as a cadet, where he served for 44 years.

After various promotions, John Sadleir was in charge of the northeastern district. Several inter-related and lawless families lived in this area, the Kellys most prominent among them.

Pursuing the Ned Kelly Gang

John Sadleir was heavily involved from the outset in the pursuit of the Kelly Gang, comprised of Ned and Dan Kelly, Steve Hart and Joe Byrne. In 1878, the Kelly Gang went beyond horse-stealing and murdered three police officers Sadleir sent out to look for. Ned then allegedly invited all the gang members to fire bullets into their bodies to implicate themselves equally.

At that point, the Kelly Gang members were declared outlaws, liable to be shot on sight. They could have turned themselves in to the police station to avoid being outlawed but chose not to.

Instead, they held up small towns in Victoria and New South Wales, locking up inhabitants and robbing banks. Then, they went deeper into hiding, as they knew the Victorian government had deployed aboriginal trackers to search for them.

The Kelly gang members greatly feared these trackers, as they possessed bushmen’s skills superior to theirs. They were also vastly more skilled than the colonial police, who were poorly paid, mounted and armed.

Betrayal Leads to the Glenrowan Siege

The climax of the affair came in June 1880. Kelly’s friend Joe Byrne, one of the gang of four, had broken cover to shoot his former best friend Aaron Sherritt dead in front of Aaron’s wife and her mother. He did this because Sherritt had become a police informer.

After that, the gang knew the Queensland trackers would immediately leave Melbourne by train to go after them. So, they quickly rode to the nearby hamlet of Glenrowan, about 150 miles from Melbourne, on the main railway line to Sydney.

They captured the only local police constable and locked him up with 50 inhabitants in a small hotel. Then, they compelled some captured line-repairers to take up rails beyond the station on a bend near a ravine.

The intention was to kill everyone on the train: the aboriginal trackers, many police officers, several newspaper reporters, and other civilians. Ned confirmed all of this to John Sadleir after his capture.

The Glenrowan Siege Goes Awry

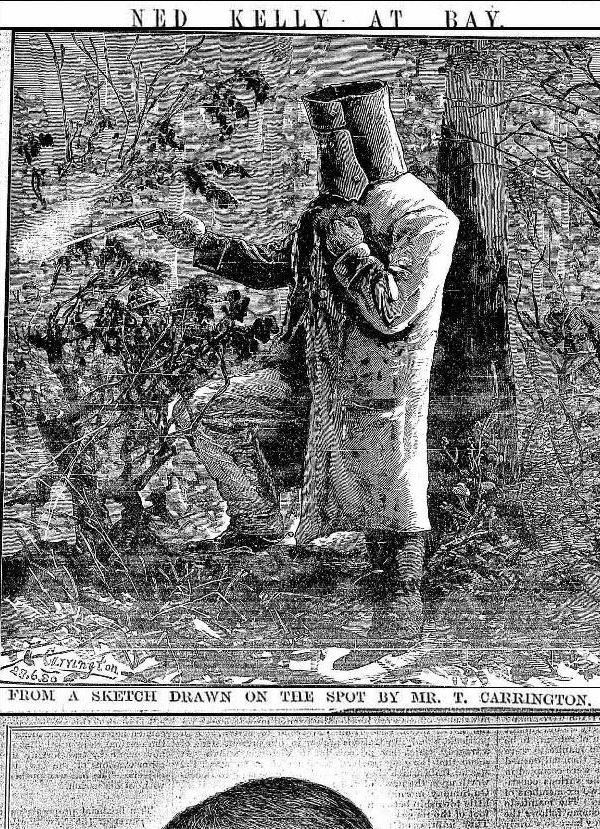

Back at the hotel, the gang donned their famous armour from stolen ploughshares, ready for a late-night attack. However, a schoolteacher managed to escape the hotel and ran to warn the train driver of Ned Kelly’s plan. He was able to stop the train safely at the station.

Then, the police superintendent on the train disembarked his men and their horses and led a charge on foot towards the hotel. On arrival, he was shot in the wrist almost certainly by Ned Kelly.

Due to blood loss, the superintendent had to retire from the scene for treatment. A reporter tied a tourniquet on the wrist and made some on-the-spot sketches of the encounter and its aftermath.

The Most Written-About Day in Australian History

It was now early morning on the 28th of June, 1880. This is said to be the most written-about day in Australian history.

The Queensland sub-inspector in charge of the trackers took temporary command and summoned reinforcements by telegraph. Then, Superintendent Sadleir arrived at 5:30 am from the nearby town of Benalla with nine more troopers and assumed command.

The besieging force now numbered about 30. They exchanged brisk fire with the outlaws in the hotel before they were attacked from behind by Ned Kelly himself. He’d managed to leave the hotel much earlier but chose to stay at the scene.

The police fired their Martini-Henry carbines, shotguns, and revolvers at Kelly, but the shots bounced off his armour. Ned was eventually brought down by revolver shots aimed at his legs. Sadleir took him to the railway station for treatment and administered two or three bottles of brandy. John had some kind words for Ned, as he thought he was dying.

Peace in Kelly Country: Ned Kelly Was Hanged

After the captives escaped the hotel, the police set it on fire. But before it burned to the ground, they retrieved the charred body of Kelly’s friend Joe Byrne, who was killed by a stray bullet when he lifted his armour to drink some whisky. The two other gang members, Steve Hart and Ned’s younger brother Dan, likely shot themselves and were burnt beyond recognition.

After recovering from his wounds, Ned was tried and inevitably convicted of murder and sentenced to death. The day before Ned Kelly’s death, he insisted on being photographed in Melbourne gaol, or jail.

Sadleir was later credited with bringing peace to the so-called Kelly Country with his conciliatory approach. Afterwards, there were no more severe bushranging outbreaks in Australia.

My Ancestor John Sadleir’s Legacy

Sadleir received the sixth largest share of the £8000 reward for the destruction of the Kelly Gang. Following the Kelly outbreak, the Royal Commission heavily criticised John and many other senior and junior officers. But most of this was set aside when the report was largely debunked.

Interestingly, John was a police colleague and good friend of Robert O’Hara Burke, who led and perished in the disastrous 1860 Burke-Wills expedition across the interior of Australia. John would have joined them but didn’t due to family commitments.

Sadleir finally retired in 1896 as inspecting superintendent, one rank below chief commissioner. In 1913, John Sadleir published his memoirs in Melbourne at 80, six years before he died. These were re-published by Penguin Australia in 1973.

A Heroic Family Lineage

Several of John and his brothers’ descendants served voluntarily in both world wars with the Australian and British armies, the RAF and Royal Australian Air Force, and British Army nursing services. Another served in the Argentine Army in the 1970s. In fairness, the descendants of Ned Kelly’s siblings have also served their country in peace and war.

One of John’s great-grandsons, Richard, is an eminent zoologist who has worked worldwide, from Scotland to Antarctica. He has two daughters who have represented New Zealand at the Olympics in synchronised swimming. Such is the rich diversity of human endeavour.

Work with the Experts to Research Your Irish Heritage

Ancestry research can reveal fascinating connections in your family’s history, like my family’s connection to the Ned Kelly Gang. You may think you know everything about your heritage. Still, digging can uncover unexpected characters who played a role in your family’s past.

If you’re interested in learning new stories about your lineage, the Irish Family History Centre can help. Contact the team of expert genealogists to start your research into Irish family history.