The Trinity College course in Irish Family & Social History resumes in September 2019.

The course runs for sixteen weeks, over two semesters, and is a distillation of what I’ve learned over twenty five years a a professional genealogist.

During the year, I encourage students to prepare blogs, short stories or snippets from their own research, using what we’ve learned in class. Michael McGee prepared this blog after our class on Wills & Testamentary records, Armed with information, he traced a surviving copy of his grandfather’s 1876 will on the P.R.O.N.I. website.

The evidence in the will answered some questions about a story in the family history, that Michael had never been able to prove before. It goes to show what you can find, when you know what sources are out there.

Fiona Fitzsimons

_ _ _

4 generations of the McGee family.

When I was much younger – back in the 1950s – we were told that our grandfather’s brother, Michael (McGee), had eloped to South Africa in 1879. The story was that he fell in love with a local publican’s daughter, Bridget Sarsfield. Michael’s two sisters didn’t approve because ‘she wasn’t good enough for him, being a publican’s daughter’.

[I thought this was ironic because each sister later married a publican.]

Michael and Bridget established themselves in South Africa and reared a large family there. The story goes that after they left, the two sisters travelled to Armagh to bring their younger brother Patrick (my grandfather), home from boarding school to run the farm.

As I began work on my family tree, a cousin told me that the parish priest persuaded Michael and Bridget to marry before they left, and had arranged a quiet ceremony for them.

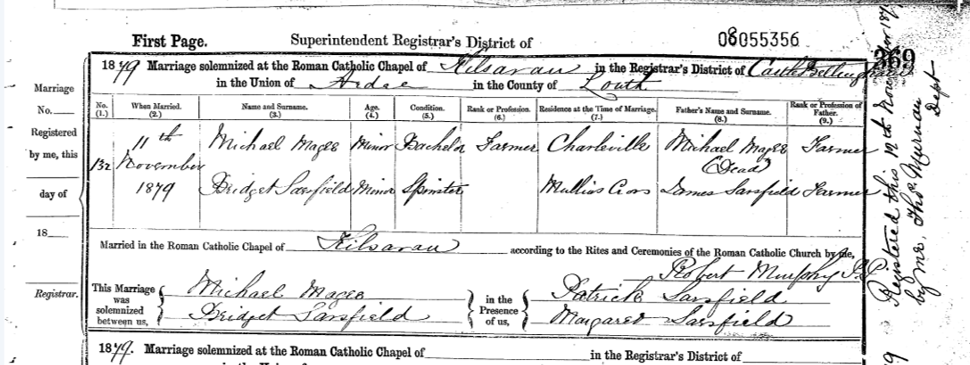

Early in my explorations I did indeed find the record of their marriage in the local parish records. The marriage record supported the story of ‘family tension’ around their union, as both witnesses were from the bride’s family.

Marriage of Michael McGee and Bridget Sarsfield 1879.

As I got more knowledgeable in my research I found that my great-grandfather, (also Michael) had made a will, still available on the PRONI website. It was fascinating to read. In 1875 my great-grandmother died. In September 1876 my widower great-grandfather, Michael Sr. made a will. He died on Christmas Eve the same year.

The will was a revelation. It answered some questions, but raised others.

Here are extracts from the will:

… I leave and bequeath to my son Michael … my farm where I reside at Dee farm consisting of 52 acres which I hold under Matthew O’Reilly Dease Esq my house and furniture, all my stock (viz) six horses, three carts, and harness (sic) three ploughs two harrows two rollers. Three milch cows, ten head of two year old horned cattle, six store pigs, a sow and litter, subject to the following conditions, that he Michael will not leave his brother Patrick and his sisters Kate and Bridget or marry a wife until he is twenty-eight years of age and should he do so to the contrary conditions set forth, he forfeits his claim to the farm and any stock which may then be on it and stock and farm revert to his brother Patrick in the event of Michael not observing the conditions before mentioned.

My great-grandfather left £600 sterling (about €85,000 today) to Patrick (my grandfather), and instructed his older son, Michael Jr., to pay the £600 into a bank account, out of the profits of the farm at a rate of £70 per year. Michael was obliged to provide lodging for his brother and sisters and to support and clothe them out of the proceeds of the farm.

Should the farm and stock revert to Patrick McGee in consequence of Michael not observing the conditions as before mentioned the portion of the £600 or the whole of it if lodged is to be handed to Michael should he please my Executors hereafter mentioned. It is my express wish that in the working out of the farm , when a sum of money amounting to £20 that it should be lodged to the credit of both my son Michael and daughter Kate and I beg of Father Joseph Healy and Father Peter Pentony to act as my Executors in carrying this my will in effect.

In 1879 Michael decided that he wanted to go to South Africa and forfeited his claim to the farm. Fr Healy was the local parish priest and Michael probably told him he was going to South Africa so that he could claim the portion of the £600 that had been saved. At that stage he was persuaded to get married before he left Ireland.

The family in South Africa kept in touch with their roots and from time to time someone visits Ireland and the old homestead, which is still in the family. Through these contacts, I was fortunate to get a brief history of how Michael and Bridget got on in South Africa:

Michael and Bridget decided to migrate to South Africa after reading a letter of a friend to his mother which was published in an Irish paper. The letter contained a vivid description of South Africa, its people, climate, abundance and variety of wild game and the lure of a possible fortune in gold mining. At that time between 400 to 500 diggers were prospecting at Pilgrims Rest, some very successfully.

They sailed from Greenore, County Louth to Holyhead (Wales) and…then from Southampton arriving in Durban in 1879. They travelled by Coach from Durban to Pietermaritzburg and from there by ox wagon to Lydenburg via Pretoria. They arrived in early 1880.

Michael tried his luck at digging for gold at Spekboom, was unsuccessful and took up a position at Lydenburg, which he held until after the first war (1881). He commenced a business of his own and carted supplies to the goldfields at Barberton. His business flourished and he then bought the farm “Schaapkraal” in the Dullstroom area. He held this for two years then purchased and settled on the farm Sterkspruit, Lydenburg. He carried out farming operations and established a grain mill on the farm (1886) and also at Pilgrims Rest.

During the Boer War of 1899 – 1902 he joined the Boers and, as a burgher, he was engaged in taking provisions from Lydenburg to Ladysmith Natal. He was taken a prisoner of war on the arrival of the British troops in Lydenburg (1899). He was marched through the streets of Lydenburg surrounded by British troops with fixed bayonets, transported to Machadodorp and then sent on to Pretoria Artillery camp where he was held a prisoner with other prominent Lydenburgers. Bridget, undaunted by her husband’s capture, started making and selling ginger beer and biscuits to the soldiers.

Through the efforts of some influential friends he was released on parole and, after spending three months in Pretoria and six months in Johannesburg, he was allowed to return to Lydenburg (1900). He then recommenced farming and milling operations at Sterkspruit.

The mill was blown up, shortly after his arrival, by the Boers who suspected him of supplying the British with meal. The British also suspected Michael of supplying the Boers with meal and in retaliation they blew up his other mill at Pilgrims Rest!

During the war the British troops looted over 130 head of cattle, 3 horses and between 700 and 800 bags of meal. In fact, they stripped Sterkspruit bare and did not even leave the family with a fowl. Undeterred, Michael started a hop beer factory in Lydenburg and did a splendid trade with the British troops! The family home on the outskirts of town was named ‘Pine Lodge” and the walls showed marks of bullets and shell after the war.

Michael was fearless, a pioneering entrepreneur and an astute businessman. After the war he started a General Dealer’s business and a bakery. He moved the grain mill into town and operated the finest milling plant in the Eastern Transvaal. He was a sworn appraiser and his main business was that of Auctioneer, Miller and Grain Merchant. In 1924 he went into the motor business (Dodge Franchise) and two years later he took over the Ford Franchise.

Michael was a livewire Irishman and made his mark in Lydenburg. He was first Secretary and afterwards Chairman of the Lydenburg Turf Club. These meetings were a great success and horses from all parts of the Transvaal competed.

He originated the idea of the sheep dipping tank. He mooted the starting up of the Agricultural Society (Lydenburg Landbougenootskap) and was a founder member thereof in 1895. Michael, as Chairman, organised the first agricultural show after the Anglo Boer War. He was later made a life member of the society.

He fought hard for electric lights for the town but failed because of strong opposition. He then installed the first privately owned electric light plant at Sterkspruit.

He was Mayor (“Voorsitter van die Lydenburgse Dorpsraad”) for several terms (1906 – 1907 and 1911 – 1912).

Michael was a foundation member of the Lydenburg Golf Club. He was Chairman for 17 years and was subsequently made a Life Member. He played golf until shortly before his death at the age of 80.

Michael and Bridget raised a family of eleven children. They celebrated their Golden and Diamond Wedding Anniversaries in Lydenburg.

Bridget died in her 99th year, at which stage her husband and all her sons had passed on. She was a pioneer in her own right. In 1952 she was honoured by the Pope with the Cross Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice for her work for the Church in the Eastern Transvaal.

As his grandnephew I am proud of his decision to leave the farm and see the world. The picture below tells it all and shows Michael and Bridget with three generations of descendants.

By Michael McGee (Dublin)