By expert researcher Carmel Gilbride

If an emigrant left Ireland before 1901, researchers often assume that’s the end of their story in Irish records. However, recent searches show the usefulness of tracing an emigrant’s parents in the 1901 Census.

Follow along to discover how you can use the 1901 census of Ireland to learn more about your ancestors. I’ll offer research tips and share how census returns allowed me to uncover my family’s story and find new relatives alive today.

The 1901 Census in Ireland

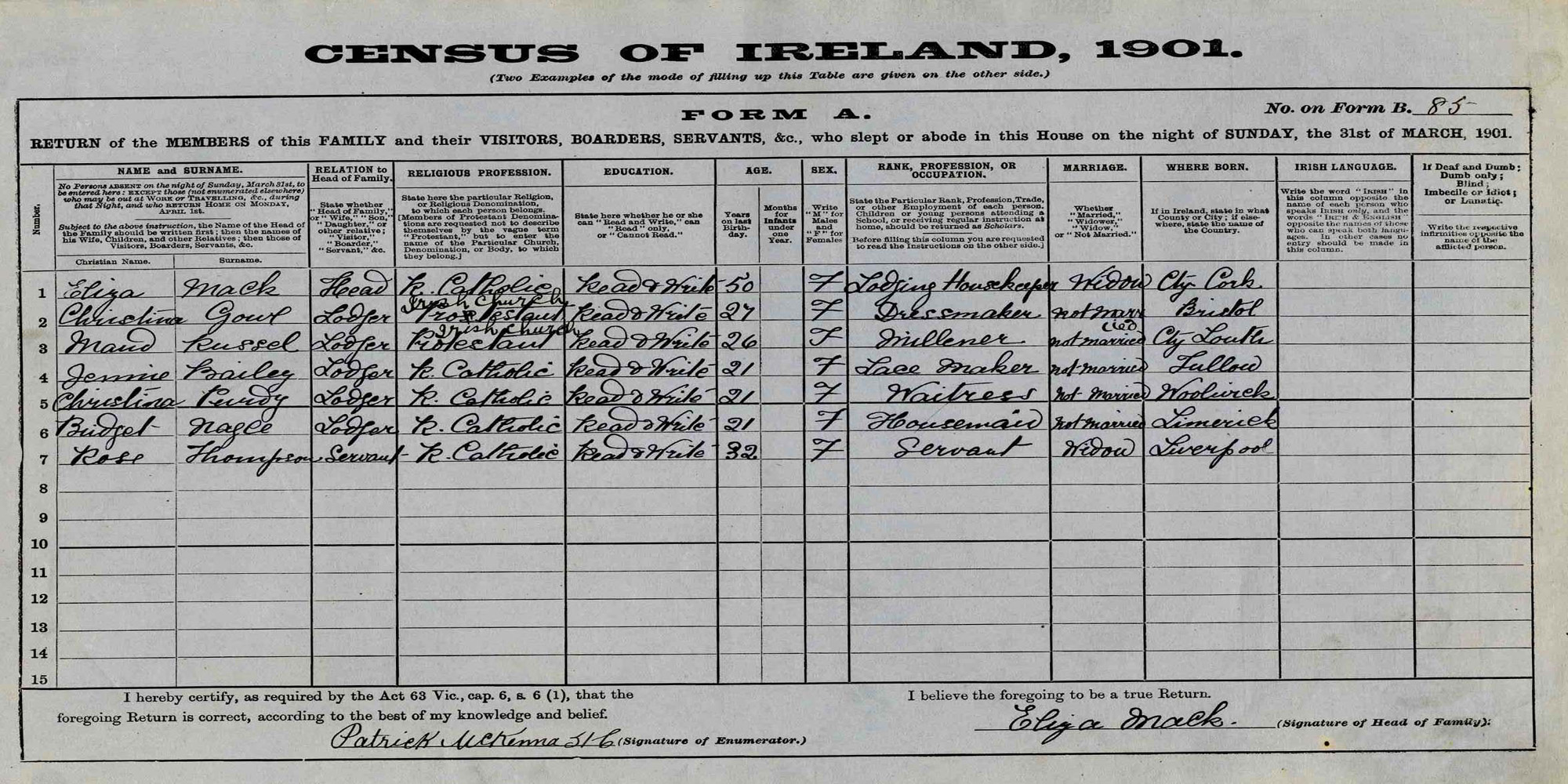

Of all the censuses of Ireland, the 1901 census is the oldest complete surviving census. These census returns reveal useful information like names, addresses, occupations, and ages of people living in a household.

The 1901 census is a goldmine of information for anyone with Irish ancestors. You can search it online for free at the National Archives of Ireland. The website allows you to search using criteria like census year, surname and forename, approximate age, and townland or street.

How Do I Find My Ancestry in the 1901 Census?

Before searching the 1901 census records, it’s helpful to know your ancestor’s name, approximate age, county, and townland or street where they lived. If you’re unsure of these details, you can try searching for other family members who might be listed.

When you find your ancestor in the census, take note of the details listed, like their age, job, and relationship to the head of household. This information will be helpful as you continue your ancestry research.

In the 1901 census, each person is listed with their relationship to the head of household. So, if you can’t find a particular ancestor, it may be helpful to search for their parents.

Using the 1901 Census to Map My Family’s History

I recently used the 1901 census to learn more about my Irish family history. My great grandmother Eliza (b. 1858) emigrated with her young family in 1888, taking a large part of my family history to the US. I didn’t realise until recently how worthwhile it’d be to search for her family in the census.

Remarkably, Eliza’s elderly mother, Ann, was listed in Ireland’s 1901 and 1911 censuses. Her listing gave me some valuable clues about this branch of my family tree.

Filling the Gaps in My Family Tree

I learned that Ann was widowed by 1901, so I now had a bookend year to search for the death and a possible will for her husband, Mathew.

The census form gave me an approximate birth year for Ann and took the family back to the early 19th century. This is around 20 years before her marriage in the late 1850s, my family’s earliest documented record.

Revealing New Details on Family Life

Because of the census, I was able to get a more intimate look at my ancestors’ family dynamic.

First, I discovered that Ann held on to the farm after her son’s marriage. Ann described herself as a farmer and head of household, including her adult son and daughter-in-law.

Additionally, the census form provided helpful information on Eliza’s siblings. They had been overlooked until that point because of her emigration.

Opening New Doors in the Present

Later, I learned that an invitation from Eliza’s maternal aunt prompted her emigration to the US. The census gave Ann an approximate age, allowing me to estimate an approximate birth year for my Aunt Lucy.

ccess to the complete census of 1901 revealed more than I had ever expected. Aunt Lucy’s estimated birth year helped me trace her in American records. From these records, I learned much more about this family branch and even connected with one of Lucy’s descendants, still alive today.

The Experts Can Help You Discover Your Irish Roots

Genealogy research is most fruitful when you explore all of the available paths. It’s wise not to discount resources like the 1901 census of Ireland, as they might reveal answers you have never imagined.

If you’re interested in learning all your options for exploring your family history, turn to the Irish Family History Centre for help. Contact us today to get the resources and expert support you need to paint a complete picture of your family’s story.