4a. 1940 to D-Day:

At the outbreak of WWII Rickard rejoined the Armed Forces, and was assigned to Combined Operations in its first incarnation under Roger Keyes who served as Director between July 1940 and October 1941.

Combined Operations drew on the best practices and expertise available within the Royal Navy, the Army and the Royal Air Force to create a unified force. Many of the Services’ top planners and experts formed the nucleus around which the Command was now formed.

In 1940 in the aftermath of Dunkirk, Combined Operations was completely reorganised under Lord Louis Mountbatten, and it developed a new focus – to plan and prepare for the re-invasion of Europe by a British (and after America entered the war), by an Allied army.

In 1942, Churchill decided that Mountbatten, as Chief of Combined Operations, should attend, on an equal footing, the meetings of the Chiefs of Staff (i.e. Combined Operations became a ‘fourth armed service’ alongside the Navy, Army and Airforce). In doing so, Churchill overturned the Armed Services established protocols. To this day almost all histories of WWII refer to Combined Operations as a temporary creation, which held an advisory or subordinate place amongst the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Although the role of Combined Operations concluded at the end of WWII, it was never intended to be subordinate to any of the armed forces, a fact supported by the official records.

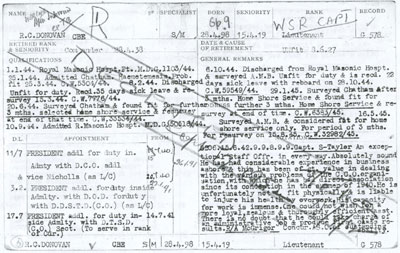

On Mountbatten’s appointment to Combined Operations, he set about introducing major changes to personnel, organisation and communications. In the following years, Rickard Donovan was rapidly promoted within the service. Rickard’s rise through the service in such a short space of time suggests that he was highly regarded by his colleagues, and comments in his service records would tend to substantiate this.

In 1942/43 Rickard was part of the Plans Division, and his service record at this time describes him as ‘an exceptional staff officer in every way’. In August 1943, he was promoted to Assistant Director of Plans with an Acting Rank of Captain. In December 1943 Rickard was again promoted, this time to the position of Deputy Director of Combined Operations, and in 1944 he was made Senior Deputy Director.

Rickard was one of the small number of people responsible for working out the detailed plans necessary for Operation Overlord (D-Day), and for directing its course. The Chief of the Division, and his commander was Mountbatten although as Senior Deputy Director it appears that Rickard took the lead on most day-to-day activities. A number of letters from Lord Mountbatten to Rickard Donovan were discovered among the family papers in Ballymore.

The strategic importance of Combined Operations to the success of the D-Day landings, can be discerned from an official communication sent by Churchill to Mountbatten [dated 12 June 1944]:

‘Today we visited the British and American Armies on the soil of France. We sailed through vast fleets of ships with landing-craft of many types pouring more men, vehicles and stores ashore. We saw clearly the manoeuvre in progress of rapid development. We have shared our secrets in common and helped each other all we could. We wish to tell you at this moment in your arduous campaign that we realise how much of this remarkable technique and therefore the success of the venture has its origin in developments effected by you and your staff of Combined Operations. (Signed) Arnold, Brooke, Churchill, King, Marshall, Smut.’

In Rickard’s own service records from the end of the war in 1945, we find confirmation that Rickard was at the centre of these developments achieved by Combined Operations. His immediate commanding officer, Captain Robert Ellis, Assistant Chief of Combined Operations, wrote ‘It is my opinion that the successful expansion of our naval amphibious resources owes much more to his [Rickard Donovan’s] brilliant work than to any other single factor. I have been particularly struck by his loyalty and patience in difficult and disappointing circumstances, when these have arisen.’ [TNA, ADM 196/120, ADM 196/146, quote from ADM 340/242]

[TNA, ADM 340/242]

Rickard Donovan, Service Record

[TNA, ADM 340/242]

What is even more extraordinary is that throughout his entire time in Combined Operations, Rickard was often gravely ill. The TB that he had contracted as a teenager aboard submarines was untreatable, and his health deteriorated to the extent that in January 1944 he had to be hospitalised for a severe case of haemetemesis (vomiting blood). He was put on forcible sick-leave by his doctor, and was only allowed to return to service for a month (subsequently extended by a month, as each month elapsed), and then only on condition that he avoid stress and long hours, an impossible requirement for anyone involved in the D-Day planning. Despite serious illness, Rickard’s active participation was seen as critical at this juncture, and Rickard’s own son informed me that his father ‘did not allow his bad-health to interfere with his war-time commitments.’

4b. From D-Day to the end of WWII:

Following the success of D-Day, Rickard continued in his role in Combined Operations, taking the skills developed there over the preceding years and applying them to south-east Asia. He was Chairman of the Eastern Landing Craft Base Committee in 1945.

At the end of the war Rickard was retained by the Admiralty

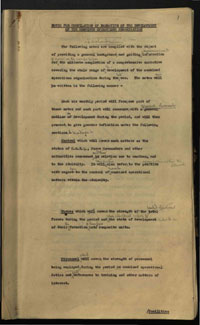

At the end of the war Rickard was retained by the Admiralty  to write a detailed narrative on the development of Combined Operations. Among the family papers in Wexford is a typescript draft copy of this history, with final revisions marked up in Rickard’s own hand.These corrections are particularly interesting, as they show a refinement in his thoughts, as he put the story of Combined Operations down on paper.

to write a detailed narrative on the development of Combined Operations. Among the family papers in Wexford is a typescript draft copy of this history, with final revisions marked up in Rickard’s own hand.These corrections are particularly interesting, as they show a refinement in his thoughts, as he put the story of Combined Operations down on paper.

In May 1946, Rickard reverted to the retired list (medically unfit) of the Royal Navy. In

recognition of his contribution during WWII,he received a CBE in 1945 by the British, and the U.S. Legion of Merit (Degree of Officer) in recognition of distinguished service to the Allied cause during the war.